Opera Gastronomica

by Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett

Published in Copia 3, no. 1 (2000): 12-14.

Opera Gastronomica

by Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett

Published in Copia 3, no. 1 (2000): 12-14.

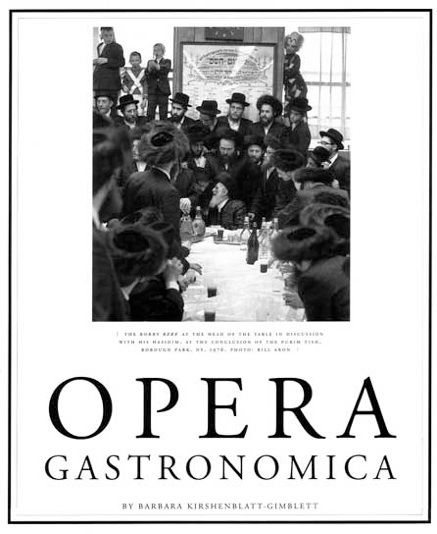

Opera gastronomica is alive and well in New York City. February 2000 brought Feeding Frenzy back to The Kitchen, a laboratory for artistic experimentation on Manhattan's west side. March brought the holiday of Purim, during which Hasidic Jews in Brooklyn performed their own form of opera gastronomica, itself a legacy of the Renaissance courtly banquet.

The musical banquet was the most "total" of Renaissance festive events. An opera gastronomica, it combined "all the arts of music, dancing, poetry, food, painting, sculpture, costume, and set design, to present a feast for all the senses." Only the orgy was more complete because it included not only eating, drinking, singing, and dancing, but also sex. With the French Revolution, such courtly practices as the banquet were supplanted by new forms of festivity and new forms of sociability.

It has taken considerable cultural work to isolate the senses, create genres of art specific to each, insist on their autonomy, and cultivate modes of attentiveness that give some senses priority over others. To produce the separate and independent arts that we know today, it was necessary to break fused forms like the musical banquet apart and to disarticulate the sensory modalities associated with them. Not until the various components of such events (music, dance, drama, food, sculpture, painting) were separated and specialized did they become sense-specific art forms in dedicated spaces (theatre, auditorium, museum, gallery), with distinct protocols for structuring attention and perception. It was at this point that food disappeared from musical and theatrical performances. No food or drink is allowed in the theatre, concert hall, museum, or library.

In the process, new kinds of sociality supported sensory discernment specific to gustation, the literary practice of gastronomy, and increasing culinary refinement. Food became a sense-specific art form in its own right and the restaurant became the dedicated space of food theatre. In the famous words of Chantillon-Plessis, "The dining-room is a theatre wherein the kitchen serves as the wings and the table as the stage. This theatre requires equipment, this stage needs a décor, this kitchen needs a plot." The menu, one might add, is "a kind of playbill, varying with the theme of the drama."

The table and the stage continue to have a shared history and future. That future is being shaped by the increasing theatricalization of restaurants, by contemporary artists who work across media to forge new syntheses, and by communities who uphold the legacy of the historical opera gastronomica.

The model for opera gastronomica--an event that is planned from the outset to integrate the arts of musical theatre and dining--is thought to be the sacred banquet and, in particular, the sung mass. The Hasidic tish is a legacy of such courtly banquets and a sacred banquet in its own right. The tish, literally "table" in Yiddish, is a distinctive Hasidic event during which the rebe, the community's charismatic leader, holds court in the house of study (besmedresh). During the tish, the rebe will bless food, deliver a discourse, lead song, and dance with his followers. It is as part of the tish that some communities perform musical plays in fulfillment of the religious obligation to gladden the heart of the rebe on the carnivalesque holiday of Purim, which usually falls in March. Purim celebrates the deliverance of Jews from disaster. In what is essentially a command performance before a regal figure, the actors play to the rebe, who is seated directly in front of them on a throne-like chair. For those in attendance, the rebe and his reactions are the center of attention, not the play, and the best seats in the house are those that afford an unobstructed view of him (and secondarily of the play). The stage is literally a physical extension of the table so the performance could be said to take place on the table itself.

The food the rebe blesses, while it includes the basic components of a festive meal, is present not for physical sustenance but for commensality. People eat beforehand. The hunger they bring to the event is not physical but spiritual. Once the rebe has blessed the food and eaten a little of it, his leavings (shirayim) are eagerly grabbed by his followers, who may well number in the thousands. The rebe's leavings have been transvalued by his touch. While the quantities presented to him are grand and the vessels are lavish, neither he nor his followers eat out of physical hunger. Nor is the food itself spectacular, though the large braided hallah, a festive bread made with white flour and eggs, is grand. Like the courtly banquets to which it is related, the tish is a multi-sensory event and food is an essential component of it, even in the absence of appetite. Like the Renaissance banquets, the tish can last all night and well into the morning.

If the tish upholds the legacy of the historical opera gastronomica, Feeding Frenzy suggests what its future might look like. In this performance, cooking is an integral part of the musical score. In precisely 90 minutes, each of four cooks prepares ten portions of ten courses. The amplified sounds of chopping, sizzling, steaming, and grinding are part of "an instructional, time delineated score," performed by four musicians on guitar, saxophone, pipa, and synthesizer. Mr. Fast Forward's "sculptural approach to creating sound" ties the sound of the objects, substances, and processes of cooking to "the physical gesture that creates the sound." We not only see the cooks. We also hear them.

Ouhi Cha performing in the European premier of Feeding Frenzy

at Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin in 1994. Photo: Johannes Zappe.

The entire room is projected onto a large screen from two video cameras that roam the space, settling for a moment on the stir-frying, the plucking of pipa strings, guests eating, waiters rushing about. Low resolution and sometimes overlapping video images wash over us. Waves of chatter, noise, and music ebb and flow. I feel like a large ocean mammal, drifting in a vast dark sea of ambient sounds and smells. All of a sudden a cook whacks a bell with a knife. A course is ready. Five waiters collect the servings and randomly serve them to us. We are seated at about twenty-five round tables for four. My senses are on the alert as a new course comes into view. Will the waiter choose our table for the margarita rolls (frozen cylinders of margarita are wrapped in Vietnamese rice sheets)? Will the mushroom matzo balls or tea-smoked beancurd skin "duck" come our way? Who will get the creme brulee in individual Chinese soup spoons (the sugary surface is torched on the spot) or the Berber seitan, rice ball geology lesson, or poached pear in kaffir broth? Time is running out. The cooks are frantic. A large digital display at the back of the room, sometimes projected on the screen, counts down the minutes. Zero. Everything stops.

Roger Fessaguet, former chef-owner of La Caravelle Restaurant in Manhattan, describes himself to me in 1989 as a conductor and his kitchen as an orchestra. The various stations parallel the strings, wind instruments, and drums. Do not expect the slow movement of a symphony from this orchestra, though Fessaguet's chefs are no less frenzied than Forward's cooks. Following Escoffier, Fessaguet's kitchen must complete innumerable dishes, with their many components, in ever changing combinations and sequences, so that each table in a room of many tables may be served what it has ordered for a particular course all at the same time, at the right temperature. Forward departs from the principles of Escoffier's kitchen in two ways. First, Foward reverses the division of labor typical of the Escoffier kitchen. Each of Forward's cooks prepares each dish from start to finish and in an average of nine minutes. Second, Forward shifts the choice of what will be eaten from the diner to the waiter. What you are served is arbitrary.

So too is the division among the senses arbitrary, according to Marinetti, who disarticulated the sensory qualities of food and reassembled them in startling new ways. His Futurist Cookbook set out the terms for an avant-garde opera gastronomica based on sensory experiences specific to food. A history of the theatre in relation to the senses—and specifically the interplay of table and stage-- remains to be written. Feeding Frenzy and the Hasidic tish are good places to start.

-

Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett is Professor of PerformanceStudies in the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University, where she teaches a course on Food and Performance. An avid collector of food and cookery books, she is working on a social history of Jewish cookbooks. Most recently, she published "Playing to the senses: Food as a Performance Medium" in Performance Research 4, 11 (1999).

-

Works Cited

"MrFastForward.com." Web page [accessed 23 March 2000]. Available at http://www.mrfastforward.com/.

Aron, Jean-Paul. 1975. The art of eating in France: manners and menus in the nineteenth century. New York: Harper & Row.

Chatillon-Plessis. 1894. La vie à table à la fin du XIX siècle. Paris: Fermin-Didot.

Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara. 1990. Performance of precepts/precepts of performance: Hasidic celebrations of Purim in Brooklyn. In By means of performance: intercultural studies of theatre and ritual. Eds. Richard Schechner, and Willa Appel, 109-17. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Marinetti, Fillippo Tommaso. 1989. The futurist cookbook. Trans. Suzanne Brill. San Francisco: Bedford Arts.

Nevile, Jenny. 1990. The musical banquet in Italian quattrocento festivities. Food in festivity: proceedings of the fourth symposium of Australian Gastronomy, eds. Anthony Corones, Graham Pont, and Barbara Santich, 125-35. Sydney: Symposium of Australian Gastronomy.

Patton, Phil. 4 February 1998. Reading between the lines: deciphering the menu. New York Times, sec. F, p. 6.

Pont, Graham. 1990. In search of the opera gastronomica. Food in festivity: proceedings of the fourth symposium of Australian Gastronomy, eds. Anthony Corones, Graham Pont, and Barbara Santich, 115-24. Sydney: Symposium of Australian Gastronomy.

The Kitchen. 2000. Fast Forward's Feeding Frenzy, Number 6 & 7, February 25 &26, 2000 [Program Notes]. New York: The Kitchen.

Home | About | Music | Video | Feeding Frenzy | Musique a la Mode | Teaching | Art | Shop | Robert Ashley